On the 3rd of August last year, I woke up early. I stood nervously with a hundred other runners in a hall in the city of Newmarket, near Cambridge in the UK. I felt intimidated as I looked at the calves, the size of champagne bottles, of the other participants. Only a few runners were starting their first 100k that morning. For many, this was not even the peak of their season. This route was long but almost flat, with only 1,000 meters of cumulative elevation. The real ultras were happening in the Alps, where long distances were combined with a crazy amount of ups and downs.

I was almost startled when the race gun fired. I had been chatting for a few moments with a runner I recognized from the 50k I completed the year before. I started running at 7 am, and I would not stop until 15 hours later, finishing the race in the dark with my headlamp guiding me.

As I took my first steps on the path, almost delighted to stretch my legs in the fresh summer morning, I thought about how this would never have happened without Adam.

Why did I do that?

Adam and I were living in the same apartment during my time in London, and we regularly went running together, taking part in Saturday morning 5k park runs near our home or running after work along the canals.

One day, he asked me if I had any plans for the upcoming long weekend, and I said no. He planned to run a marathon by himself along the banks of the River Thames and invited me to join him as if it were a movie screening. I thought I could always stop at any point if it became too hard and take the tube back home, so I accepted. This is how I discovered that my body was particularly well-suited for running long distances without dedicated training.

I became curious to see how far this newfound ability could take me. So I continued to follow Adam and signed up for my first proper ultra marathon, the SVP50, the little sister of the SVP100 that he signed up for. The SVP50 went even better than the marathon organized at the last minute. It turns out that easy access to hydration and food along the way is a game-changer.

For this new edition of the race, we were supposed to run the SVP100 together. However, he injured his leg a few days before and had to make the difficult decision not to participate. So I was alone, holding the flame on that August morning, about to conclude my journey of discovering how far I could run.

Though that was not my sole motivation.

After my first marathon, I became fascinated by the mental state one reaches during long runs. It is a sort of trance where the complexity of the world dissolves, and your sole purpose in life becomes putting one foot in front of the other and getting to this arbitrary point you decided would be the “end”.

I also enjoyed finding a space where I could explore the surprising achievements my body could complete while putting my brain on the backseat. Knowledge work makes my brain the king organ, while the rest of my being is relegated to a “support role” that needs to stay active through exercise.

Leopards sprint faster than any other animals, and giraffes have necks long enough to reach the most inaccessible leaves; humans’ running endurance might have been one of our strengths as a species, allowing us to chase prey to exhaustion. We might have bodies (and psychologies) specifically fitted for long runs. I enjoyed stepping into this more animal side of being human, feeling a sort of closeness to my ancestors. The trance I experience during long runs is probably something I could bring up if I were to spend an evening catching up with them around a campfire.

Running worlds.

I must say that I did not prepare properly for this race. Or at least, I didn’t prepare physically much. I run a few kilometers every week and did a trial marathon two months before the race. I bet everything on mental preparation. I needed a way to grasp what a hundred kilometers would feel like so I could project my motivation at the end of the race and not feeling during the race, “I thought it would be over by now, but I am still running.”

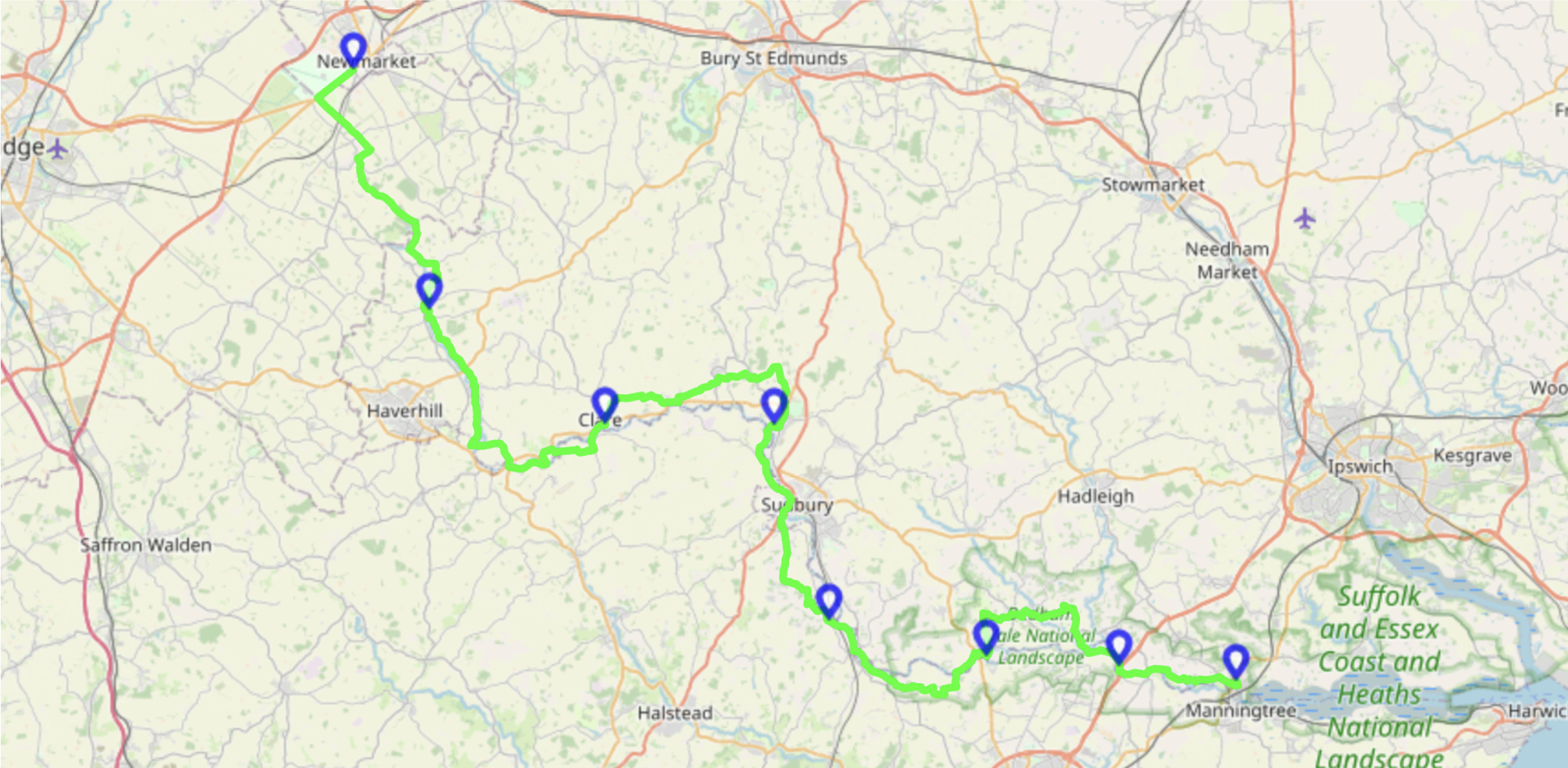

I decided to solve this problem with mindware. I split the route into seven pieces, the chunks in between the blue pins on the map above that mark the aid stations along the way. For each chunk, I built a mental world that I would construct mentally on top of the environment I perceived, with themes freely inspired from the worlds in Mario Bros.

There was the lava world, where the rivers I crossed were currents of melted rock bubbling and projecting incandescent droplets around. The ground was charred. After each step, I imagined how my foot caused cracks in the ground through which I could see the lava coming out.

In the ice world, the trees were thin spruces and pines. I would imagine the people I meet as Inuit covered in fur coats. The bricks of the buildings were swapped for ice cubes, igloo-style. I reframed the stiffness of my muscles as my sweat crystallizing, making my movements harder.

This imaginative exercise was a fun way to pay attention to the environment during the race, though the mental images I created were not very vivid.

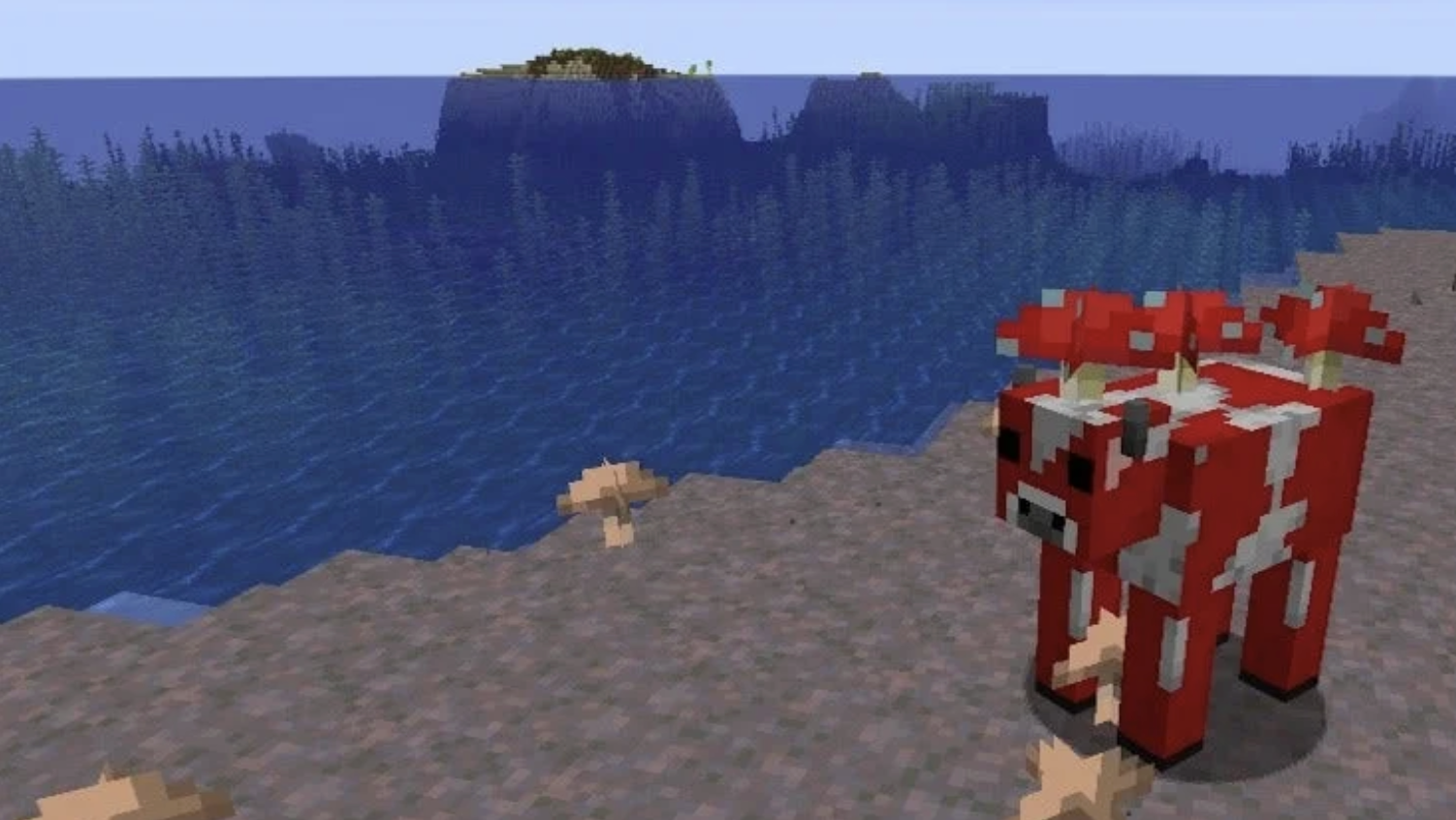

The road became filled with small puzzles. I tried to turn elements from the environment into the world I was imagining. I would meet a cow in the mushroom world and recall from a forgotten part of my memory that I had the perfect mental image for this crossover coming from my Minecraft experience. I would ask questions like, “What should streetlights be in the marshland world?” and make up wooden beams covered in vines, with giant fireflies sitting on top.

As the race unfolded, the worlds became harder and harder to construct in my mind, and eventually, they only surfaced sporadically. Instead, something else took their place. The pain.

The pain.

I reached kilometer 50 around midday in good shape, running at an average pace of 8.5 km/h during the first half. However, my condition deteriorated from there. I started feeling strong cramps in my quadriceps that, fortunately, subsided after some time. After 70 kilometers, my feet began to hurt. They swelled more than I expected, and my shoes turned out to be too small for them. These last kilometers were the most painful experience of my life. This experience stayed with me, even a year after the race. It made me more open to understanding, at a visceral level, how much suffering one can endure.

At the 80-kilometer mark, I took a long break at the aid station and asked for support from a nurse. She pierced the blister on my foot and gave me painkillers. In the calmest voice, she announced that the blister ran too deep and that I was likely to lose the nails on my little toes permanently. The prospect of irreversible bodily impact (even as small as this one) made me consider whether I had pushed myself too far. But the nurse boosted my morale and advised me to keep running. She shared her experience providing emergency health support to migrants in the Dunkirk refugee camp. I think it had the intended effect, as I began to feel that my situation was not as desperate after all.

So I continued the race. I picked up two sticks by the side of the road and finished the race walking with my improvised poles. Over the last 20 kilometers, my pace plummeted to only 5 km/h. I was racing against the clock to make it to the last aid station before the cutoff time. I arrived 45 minutes before the cutoff and had the pleasure of meeting Adam, who came all the way from London to cheer me on at this final checkpoint. After this boost in motivation, I finished the race in 14 hours and 51 minutes, 40 minutes before the final cutoff.

I am not running alone.

The most important lesson I took from this race is how it forced me to incorporate a long-term perspective into my actions. I was not running alone. How I felt at kilometer 60 depended on how well I handled hydration over the previous kilometers, how I forced myself to carefully chew thee salty potatoes I ate at kilometer 30, even when I was not hungry. My knees felt good because of all the attention I had been putting into unfolding my steps with minimal impact on the ground.

As I ran, I felt grateful for my past selves that brought me to where I was, and I imagined my future selves as I strived to do what was right for them to continue running.

During such a long race, no mistake is allowed. This brought me clarity and rigor in thinking about actions that don’t benefit me directly but are vital for my future selves.

I feel this mindset generalizes well to other parts of my life, where I need to coordinate the actions of my selves across timescales of months or years instead of hours. I try to cultivate it every time I procrastinate on scheduling an appointment with the doctor, when I am tempted to skip a language learning session, or when facing any hard tasks that I know are the right thing to do.

After the race.

The race put my body in a strange place. I had little appetite for the two days following the race, and I experienced hour-long hiccups. My whole body was stiff, forcing me to walk at a pace that made me empathize with the older people I used to be annoyed by as I struggled to pass them on the sidewalk. Fortunately, after a few days, these symptoms stopped, my muscles allowed me to start walking mostly normally, and I recovered completely from the race in about a month (though I continue to try to empathize with older people’s slow walking pace).

As the nurse warned, I lost the nails of my little toes. In fact, I lost all my toenails except for my big toes. However, contrary to her prediction, they all regrew over the year following the race, and I am now enjoying a full set of healthy toenails (except for one of my big toenails, which is in regrowth mode due to an unrelated event I will refrain from sharing, as this might already be too many toenail stories for one post).

Will I run more ultramarathons?

I ran one marathon after this 100k, and I might do more in the future, as I still enjoy the trance state that comes with long-distance running. However, I will most likely not go further than 100k. These might have been the most impactful 15 hours of my life; they gave me a strong baseline of self-confidence in my body and a visceral understanding of pain. I feel I can now put this chapter of long-distance running aside and take on new challenges in other domains of my life.

Want to hear when I post something new?