This post is the first part of a two-part series introducing the vision for Live theory, a design paradigm that leverages AI to build a decentralized, context-sensitive infrastructure. In this first part, I start by describing the unreasonable efficiency and the limitations of systematic thinking, the tool that live theory aims to replace.

The birth of systematic thinking.

Before the scientific revolution, intellectual progress could not scale well. People would have ideas about the world, make hypotheses and test them, gathering insight along the way. This would happen organically, without a deliberate understanding of the process itself. This is how craftsmen would learn to make stronger metals, painters would discover new pigments, and farmers would tweak their methods to be more effective. However, the main way to share this accumulated tacit knowledge was through apprenticeship, by an extended period of training with someone.

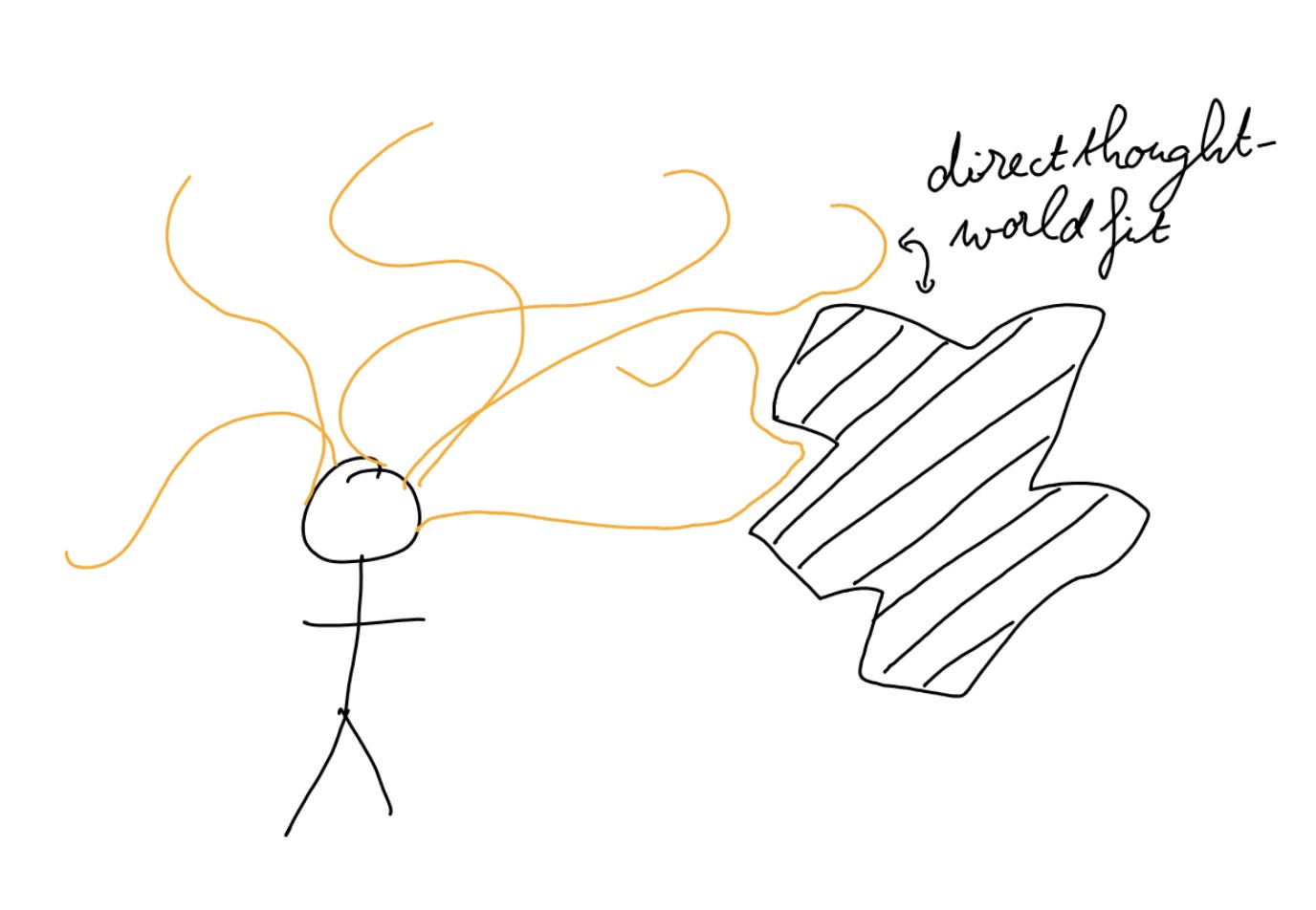

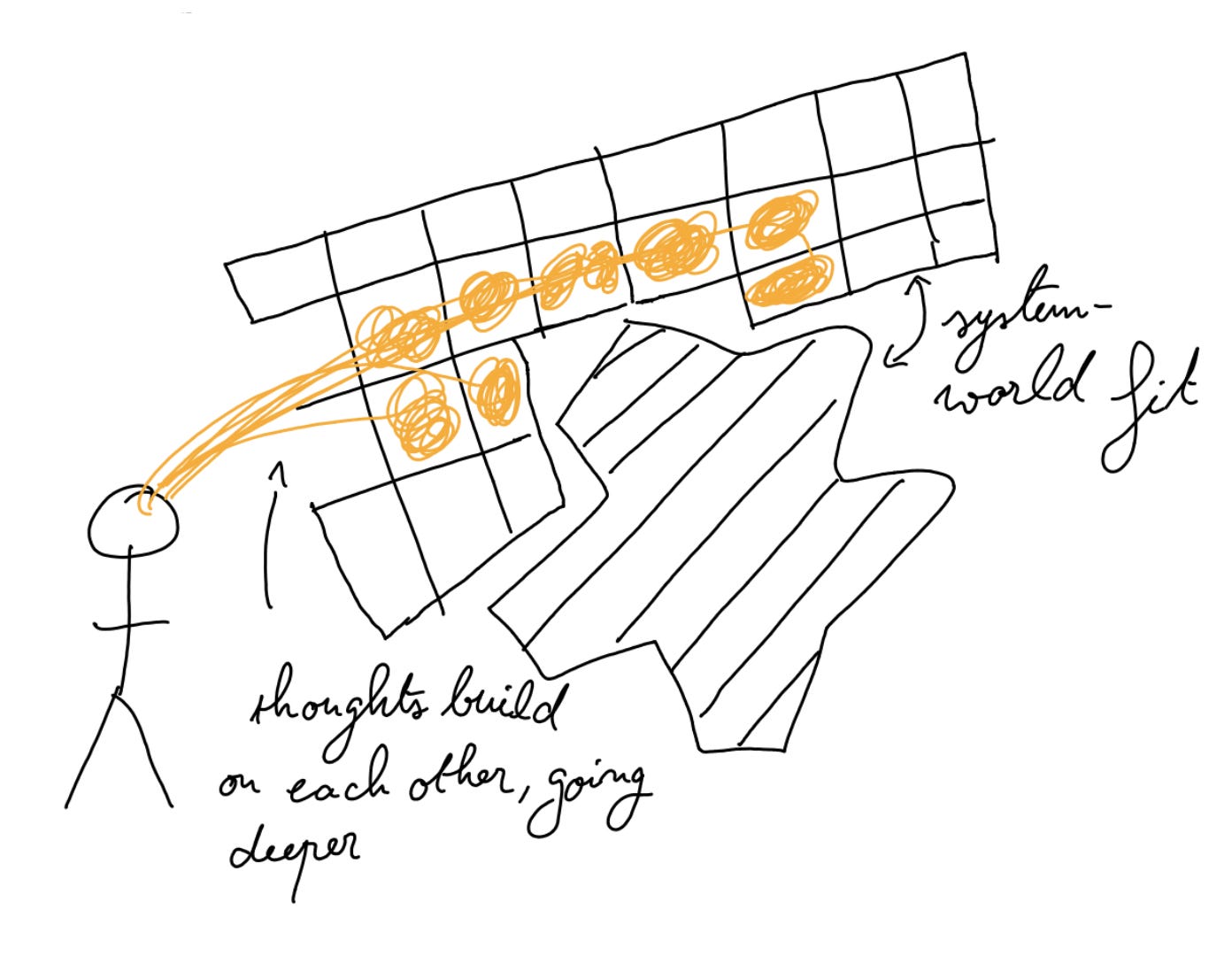

During the scientific revolution, we broke out of this trend by adopting formal, systematic thinking. Formal systems created bricks for thoughts. They filled two remarkable functions:

- Stacking thoughts on top of each other to build deeper, more complex thoughts in an individual’s mind.

- Stacking thoughts across people, so you can reuse the solutions from strangers who use the same formal system.

Lens for the thoughts.

Formal systems are sets of rules that constrain what counts as an allowed move or not, just like the rules of a board game like chess. But instead of defining rules for moving the piece on the board, a formal system gives rules for manipulating symbols, like when writing equations.

The rules of the formal system are designed to enforce consistency constraints that make the thoughts more likely to be true. For instance, the sequence of moves “0 = 1” is not allowed, as you cannot have at the same time zero apples and one apple in a bag.

This means that when using the formal system, you don’t have to think about the fit between reality and thoughts anymore. Following the rules became a proxy for what constitutes a “true” thought, a thought that matches reality. This removes the need for costly, noisy experiments. By using the system, your thoughts start to morph to follow its allowed moves. Like an optical lens, it focuses your thinking power in a tiny subregion of possible thoughts, allowing you to craft complex thoughts that would never have been possible before.

This is not to say that all valid moves are useful. Like in chess, most valid moves are unlikely to make you win. There is room to develop skills and taste to navigate towards the interesting parts of the system, the ones likely to establish non-trivial results.

Going collective

The killer application of formal systems is collective: no need to spend time as an apprentice to share insights anymore. The conclusions from the system, such as physics equations, are context-independent. They can be used without needing to know how they are produced. You can reuse a proof of a theorem and apply it to your own mathematical problem without needing to know the history or the author of the proof.

Going meta

The scientific method created a meta-system, a formal system providing rules for the game of “producing systems that match a part of the world”. It described what counts as an allowed experiment and a valid interpretation of experimental results. In its general form, it is not very usable, so fields like physics and biology developed their own formal standards to define what counts as a valid new unit of knowledge to be added to the literature. Despite dealing with experimental data, the scientific methods provided the same benefit as mathematics. As long as a paper meets the field’s systematic criteria, it can be trusted and its results reapplied in new contexts.

This methodology worked really well. Like really, really well. Thousands upon thousands of scientists around the world had the tool to develop deeper thoughts and share their progress with one another simply by sending letters. Formal systems formed the information highway that connected individual scientists and engineers from across the globe into a collective giant brain of ruthless efficiency.

All this knowledge production was put to work to solve real-world problems through engineering, using the insights from science to produce machines that solve problems for citizens. The systematic intellectual work is bundled into context-independent artefacts that enable efficient communication between knowledge producers and consumers at all levels. The engineer doesn’t have to know where the physics equations come from to use them in their blueprint, the worker in a factory doesn’t need to know where the blueprint comes from to assemble the pieces, and the end user doesn’t have to know how the machine has been produced to solve its problem.

Globalized capitalism was the system that organised the worldwide distribution of scientific knowledge. Like the scientific method, it connected millions of actors into a single collective brain. However, the information highway, in its case, did not happen through direct sharing of solutions (as these are competitive advantages); it was the sharing of value information. Capitalism provided money as a unified proxy for determining which company is successful at solving its customers’ problems. It would steer capital investment towards the most successful actors, allowing them to grow further and apply their good solutions more broadly. It created a continuous worldwide Olympics game in the discipline of “solving problems people are willing to pay for”.

The map bends the territory

At the start, around the time of Newton, systematic thinking worked because of the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics to describe the physical world. It turns out that many phenomena in the physical world, from planetary motion to heat transfer to quantum physics, can be described very well using equations.

But over time, the incredible success of systems spread far beyond maths and physics. They got applied to the social world with game theory, to organisations with Taylorism, or to agriculture. Instead of purely describing the world, we started morphing it to fit the systems. After all, this is a good strategy to make use of this abundant knowledge machine. When the system’s conclusions don’t apply to the real world because the fit between the system and the world is poor, we adjust the setup so the world better aligns with the system. This way, we gained enormous control over the physical and social worlds. This is what led to the modern financial system, monoculture, and assembly lines.

The blind spot of systems.

Remember how I said that systematic thinking worked by concentrating thinking power in a tiny subregion of possible thoughts? Well, this is both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness.

We trained generations of knowledge workers to morph their thought patterns so they would fit the right angles of the systematic maze. By spending so much time in the maze, it becomes hard to think outside of this frame, forgetting that this is a tiny subregion of possible thoughts. In fact, systematic thinking is also blind to all our inner experiences that are not thoughts: body sensations, emotions, intuitions, tacit and embodied knowledge.

More generally, despite its great success in describing the natural world, systematic thinking hit a wall when applied to problems involving living beings, such as organisms, ecosystems, or societies. In these domains, the territory is strongly pulled to fit the systematic map (like in monocultures or economics), as the map is too rigid to adapt to the world.

You cannot describe in abstract terms what health means for an organism or an ecosystem, or what fairness means in a society. It is because in such domains, context matters. There is no abstract theory of health nor fairness to be found. Fostering health or fairness requires solutions that adapt to context with a fluidity impossible to achieve with systematic artefacts, no matter how many parameters they include.

In short, systematic institutions are unable to care for life. They are great at providing abstract knowledge and material comfort, but they cannot be adapted for human flourishing and are ill-suited to address the challenges of our time, such as climate change or the socio-technical problem of AI safety.

Intermediate conclusion

Around the time of the scientific revolution, systematic thinking was designed as an infrastructure to allow scalable intellectual progress. It can be seen as a mould that makes thoughts stackable by providing a set of rules on symbol manipulation that acts as a proxy for truth. It allows individual thinkers to think more complex thoughts and share their results without having to transmit the context where they were developed.

This basic innovation served as the basis for creating a unified, worldwide, distributed cognitive system, in which millions of humans could contribute to solving scientific, engineering, and economic problems.

However, these systematic institutions can only design context-independent solutions. This makes them ill-suited for caring for beings, for which there is no abstract solution.

Transition to part II: adding AI to the picture.

The development of AI would, by default, turbocharge these systematic institutions, amplifying the downstream harm from their inability to care for beings. We need a new way to make intellectual progress scalable that doesn’t rely on systematic thinking and allows for context sensitivity. The cheap, abundant and reliable fluid intelligence stemming from AI might provide the backbone for such an infrastructure. This is what we will explore in Part II, with the introduction of the vision of Live Theory.

Want to hear when I post something new?