EDIT: Thanks to feedback on the post after its publication, I underestimated how easy it is to see your reflection in water. It is likely our ancestors did in fact know their face, maybe a bit less clearly than we do today. Interpret the post more as a metaphor!

When you are born, nobody knows your face. And in particular, you don’t know your face.

As you grow up, you become familiar with your face, observing how it slowly changes, with its pimples coming and going. This ability hinges on the peculiar fact that you have access to images of yourself, mainly from mirrors and photos.

But these are both relatively recent inventions. The first daguerreotype portrait was taken in 1839, and the earliest traces of manufactured mirrors were polished obsidian found in modern-day Turkey, dated to 6000 BCE. So, ten thousand years ago, your options for seeing yourself were:

- A still lake or rain puddle

- Looking into someone’s eye

- A naturally shiny stone

- A smooth sheet of ice

And… that’s pretty much it. Your face used to be how other people knew you. It must have been common to live your entire life without knowing what you looked like.

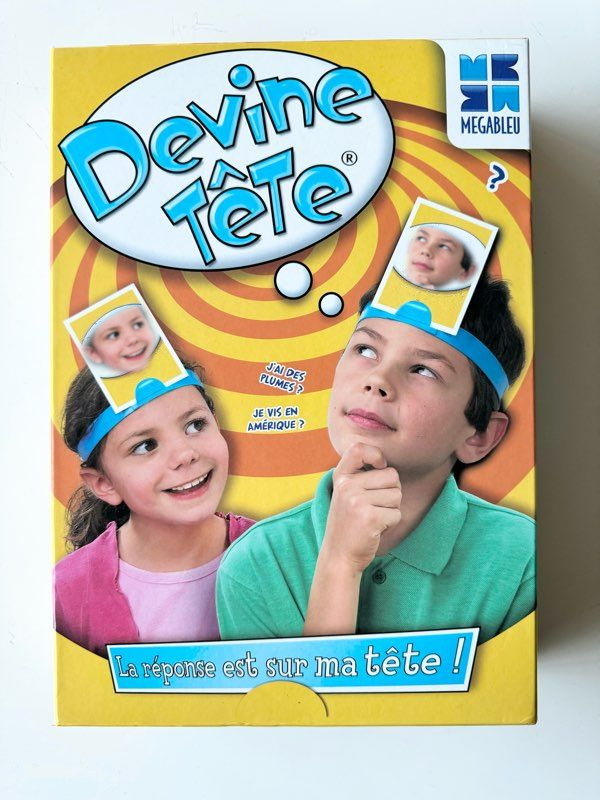

But the primary way you would get to know yourself was through the reactions of your peers around you. It is like playing the game “Who am I?” (“Devine tête” in French), with the character you are trying to guess being your face, and the game lasting for all your life.

The experience of getting to know your face, ten thousands years ago

The experience of getting to know your face, ten thousands years ago

To get a sense of what it feels like to see your face in such a world, we can look at the effect of listening to a recording of yourself. People in your life are intimately familiar with the sound of your voice, but you are familiar with another voice. This is the sound of your voice when it reaches your ears through your head instead of through the air.

We all have had this cringe experience: is this what I sound like? Our sense of self gets challenged, this weirdly foreign voice is supposed to be me? This might be the feeling shared by one of our ancestors ten thousand years ago, casually going for a walk to pick berries after the rain and stopping in shock, looking down at a puddle.

Today, our face feels like a universal way to say “this is me.” It shows how flexible our sense of self is. It is like a bag whose boundary can expand to include objects through ownership, people from our tribe, or ideologies and beliefs.

Knowing our ancestors didn’t know their faces can help us keep our identity small. It can allow us to take a step back when we hold on strongly to a cause that feels so close to our hearts, so close to who we are. Does letting this go feel worse than forgetting your face?

Want to hear when I post something new?