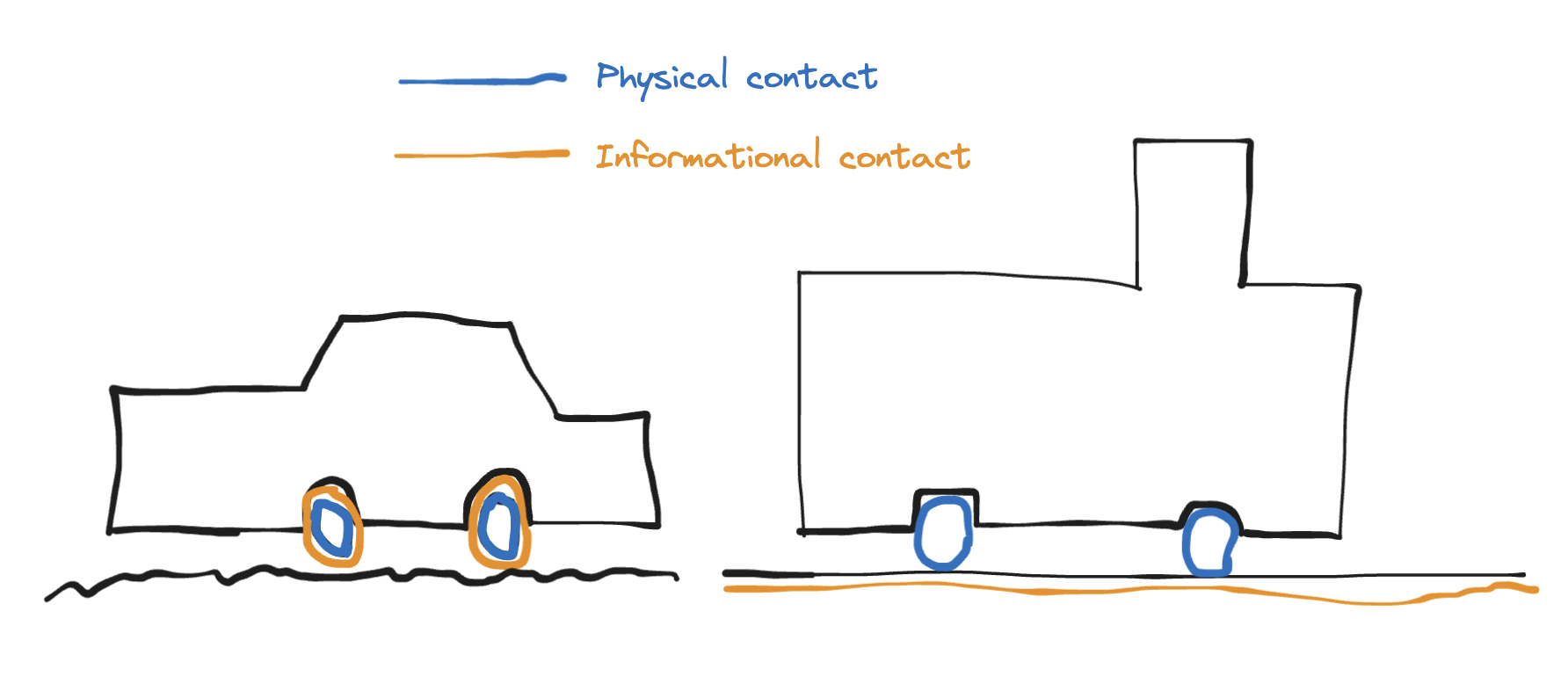

Car wheels have tires, circular inflated bands of rubber where the vehicle comes into contact with its environment. Tires are flexible because roads are unpredictable. If there is gravel on the track, a small rock, or if the car rides over a sidewalk, the tire temporarily wraps around the shape of the unexpected encounter, uses it as a point of contact, and continues on its way. I will call this the informational surface of contact, where the vehicle can adapt to the uncertain information about its environment. In the case of a car, the informational and the physical point of contact are at the same place.

The more uncertainty about the terrain, the more the wheel has to adapt. This is why all-terrain cars have larger wheels as they allow the car body to be further from the ground allowing for big rocks to pass through, and it is common to lower tire pressure when going off-road.

On the other hand, train wheels are made of steel. Sure, trains still have dampening mechanisms to smooth the vibration of the wheels against the track. But trains can’t handle nearly as many terrains as all-terrain cars.

Contrary to the wheels of an all-terrain car, the physical point of contact between the train wheel and the rails is not where the train comes into contact with its environment. The contact was established long before any train was on the track!

The first contact happens when engineers trace a path of minimal resistance through the landscape, boring machines pierce tunnels through mountains, and factories manufacture perfectly straight beams of steel. The uncertainty about the environment the train will encounter has been reduced to such an extent that non-steerable steel wheels are all that’s needed.

In other words, rails are the equivalent of infinite radius car wheels, as illustrated in the intro figure. The surface of contact with its environment spreads all along the rail lines instead of the circular surface of the wheels!

Of course, the story is not so clear, and the informational surface contact of cars cannot be traced back to a simple physical surface. The steering system, the dampeners, the human at the steering wheel, and the paved road are all doing important work to adapt the vehicle to the environment.

I think this is a good illustration of amortized investment. Trains start with a big one-off investment to prepare the terrain, so they can afford saving in design complexity and physical friction, enabling trains to go faster and be more energy efficient.

All-terrain cars, normal cars, and trains can be placed on a spectrum of different trade-offs: from highly constrained environments that allow for minimal uncertainty to vehicles that can drive in many environments, at the cost of being slower and more complex.

This story is about understanding our intuition behind the words “soft” and “hard.” If you look around you, you can notice the expectations every object carries with it. Behind each object made of soft or flexible materials such as cushions, elastic gloves, clothes, fingertips, and buttocks, there is an uncertainty and a welcoming of the shapes they will encounter during their lives.

Behind each hard object such as industrial arms, screws, chairs, and bones comes an assumption about the world that will come to meet the object. The object expects the uncertainties about the world to be handled by a process outside of itself, which could be a softer object bending or by only encountering hard objects of the right shape.

I think this intuition might provide a useful lens to look at other spaces where we bring the hard /soft metaphor, for instance, soft vs. hard personalities.

Could we also interpret idioms like soft/hard skills, soft/hard power, software/hardware this way?

Want to hear when I post something new?