AI is changing the way we interact with online content. There are the gloomy waves of AI slop, the TikTokification of video content, the ad-maxing-prompt-injection-cyberwar, yes, but also the prospect of fulfilling the web’s promise: making content come to life.

From TV to YouTube to …

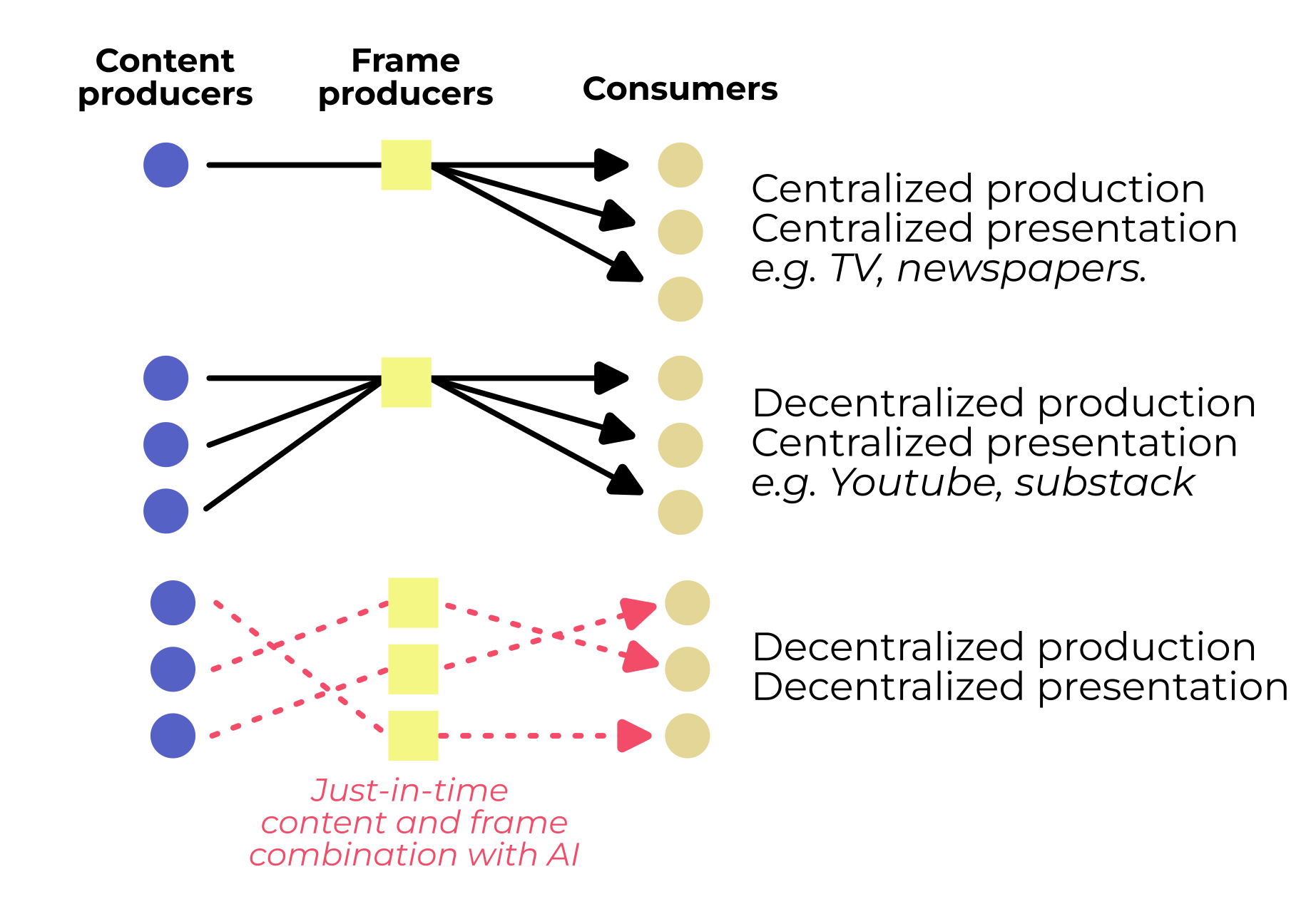

I am particularly interested in how AI can open an ecosystem of new ways content can be presented. The web broke the centralization of content production enforced by TV channels and newspapers, allowing anyone to become a content creator. The big platforms offer different expression media: blog posts on Substack, videos on YouTube, short forms on TikTok, photos on Instagram, etc. But platforms continue to enforce an economic centralisation, controlling the redistribution of revenues from advertisements. And beyond their economic power, platform continue to enforce a centralization on the presentation of the content.

Content is forced to fit within the constraints of the platform: a video, a blog, a short form, a tweet, etc. Everything surrounding the content is the territory of the platform. There is the feed controlled by recommendation algorithms, the visual design of the website (with maybe some minimal control to change the theme). Some creators experiment with new content forms, like interactive visualizations, but they are published on their own small distribution platforms, like personal websites.

On top of that, platforms distribute content in a static form. Even if a video creator finds a cool new way to add subtitles to their video, you will not be able to apply the same effect to another video. The choice of presentation of the video and the content of the video are packaged in a single file and cannot be decoupled.

AI for just-in-time combination of content and presentation.

AI presents the potential to break free from this centralization of presentation. It could allow end users to “re-flow” content to be displayed in another frame, like applying a font to change the presentation of a book. The new frame doesn’t have to follow the constraints of the platform where it was originally posted, nor the intention of the creator.

This ability to “re-flow” can give rise to a new niche of online creators: framemakers—specialists in crafting content presentations, rather than content producers. Frames could be a new form of talent specialization, removing the need to find the intersection of people who are good at knowing what to say, as well as how to say it. The what and the how of the content can be produced independently and combined at the very end of the distribution pipeline to fit the preferences of the end user (the red arrows in the diagram above).

Alongside online creator remuneration, we would need to invent new systems to remunerate the contributors to the frame in which a given piece of content has been displayed. Moreover, as we needed to design recommendation algorithm to filter the content presented to a user, we would need to create frame markets that match a given piece of content with the appropriate frames to render it. The frame-content matching would take into account the user’s frame preferences and the content creator’s frame recommendations.

I am excited about the potential of framemaking for differential technological development. Good frames for engaging with complex topics have the potential to make difficult ideas more widely accessible and raise the quality of public discourse.

This vision of framemaking has been one of the guiding principles for my work on AI interfaces over the past year. I worked on adding new options to interact with ideas in static text: Bird’s eye view re-flows corpora of text to render them as an interactive 2D map, and breaking books turns the content of a non-fiction book into a collaborative board game.

In the rest of this post, I present a list of micro-visions for new forms of online experiences. For most of them, you can imagine the backend as a web browser extension that manipulates the content of a webpage before it is rendered to the user by calling multimodal input-output AI models. The AI models are faster, cheaper, and more reliable than those available today, but not radically more intelligent.

Though, I believe many of them can be realized with today’s technology. If you feel inspired to implement one of these visions, please go forth, and feel free to get in touch!

Micro-visions: Content augmentation.

Micro-visions that preserve the original form of the content but add to it. Today’s examples include community notes that add important context to controversial tweets, or Orbit, a tool to integrate spaced repetition prompts into a text.

Interactive event timeline.

You are reading an online article describing a succession of historical events. It could be discussing the formation of the ocean in Earth’s history, the rising political polarization in U.S. politics, or the eventful weekend leading to the OpenAI battle of the board.

As you follow the article, an automatically generated interactive timeline remains on one side of the screen. When you hover over a piece of text, the corresponding part of the timeline lights up. When you click on the timeline, you can jump to the parts of the blog that discuss this piece of the story.

Interactive demos in scientific papers.

You open an ArXiv paper modelling the impact of climate change on rising sea levels. Along the text, an interactive demonstration is rendered in your web browser, showcasing the quantitative model proposed by the authors. It has been created on the fly from the open-source code and the content of the paper. You can tweak the CO2 emission curve, and see how the land mass on the world map shrinks as a result. This allows you to check the conclusions of the paper and identify blind spots in their analysis.

Interactive articles are an effective medium for explaining complex ideas. However, they are incredibly challenging to create, as they require the combined skills of designers, scientists, and communicators. In this vision, designers and communicators creates “demo prompts” that are applied to classic PDF scientific papers to transform them into interactive mediums.

Just-in-time diagrams.

You open a long X post making an argument about the money flow between various AI companies, claiming that AI is an economic bubble. The names of the different companies are highlighted in different colors, with their logos attached. Along the text of the tweet, there is a diagram generated to illustrate the flows described.

Distillation through analogies.

You are an economist reading a biology paper about genetic drift. The paper is enriched by analogies that bridge the two fields, allowing you to apply your economic intuitions to the concepts presented. The paper explains that when a population of organisms is too small, suboptimal genes might end up being propagated through random luck due to a lack of genetic diversity.

The analogy-maker adds that it is similar to the lack of competition in a market; when a certain good is produced by a few producers, the end product tends to be suboptimal in quality or price because of the lack of competition. You can expand the analogy to see the mapping: gene fitness <=> product quality and price, economic competition <=> natural selection, population size <=> market size. You also read the limitations of the analogy: the lack of competition can be exploited by companies to intentionally compromise on quality and raise prices leading to even worst products, while the effects of genetic drift occur through random luck.

From reading to deck-building.

You open a long essay making the case for a decrease in energy availability over the next few decades.

The text is broken down by quotes extracted from the essay and rendered on cards with a visual background that supports the vibe and content of each quote. All the cards in the article have a coherent style; it’s as if the author designed a visual identity for their work. Concepts introduced in the article, such as “energy descent” and “link between fossil fuel and GDP,” are displayed with symbols near the keywords and reused in the card visuals.

As you read, you can add cards to your inventory. These are the cards you want to take away from the article. However, you only have a few slots available. If you want to pick up more cards, you need to let go of others. This friction forces you to compare the different quotes to find the best ones.

Near the cards, you see small versions of related cards that you picked from previous readings. You can choose to reinforce the link of the suggested card or remove them if you find the connection irrelevant. You also see cards that come from a group collection you are part of. You discover that a friend has been reading another piece that makes the case for nuclear fusion reactors capable of supplying energy at scale in 20 years, contradicting your current article. You decide to bookmark this other article for later and send a message to your friend to ask what they thought of it, initiating a debate.

Every month, you curate the cards from your gallery to find the most important quotes you have read over the past weeks. The content of the article comes back to mind quickly as you recognize the visual style of the articles and their associated symbols. This allows you to reflect on the impact that the different pieces have had on your opinions. You curate the cards into a monthly deck, which gets added to your profile and sent by email to your subscribers.

Groups of interest also hold regular retrospective sessions to collectively curate the content its member have been reading.

Micro-Visions: Content Reframing

Micro-visions that don’t preserve the original presentation of the content can be both promising and potentially scary, as the reframing has the potential to strip the content of its intended meaning. These visions are conditioned on good execution of the UX and reliable AI models.

Contemplative reading

You open Vitalik’s My techno-optimism manifesto. Instead of being presented as a blog post, you see a single page filled with a watercolor depicting a little boy running away from a bear. The page contains simple sentences and plenty of whitespace. There is no wall of text in sight; you have space to hold all the text in your head and contemplate what is being said. You click through the pages, navigating a distilled version of the article, blending quotes from the original text, high-quality generated text, and beautifully relevant illustrations.

For an example of an online contemplative reading experience meshed with generated images, see Amelia Wattenberger’s Interface Lost Their Sense. Robin Sloan’s Fish a Tap Essay is also a good example of a contemplative reading experience.

Socratic content

You open an article, and you see a single sentence stating “Books don’t work” with a text area underneath. The sentence is a provocation, and you must provide your opinion to continue reading. You argue against the opening statement: books work; they are a very effective medium for storing our collective memory. The article responds to your points by asking further questions and showing quotes from the original text, clarifying what is meant by “don’t work”: reading a book doesn’t necessarily translate to internalized knowledge.

You go back and forth to explore everything the article has to offer in a debate. This process allows you to skip the points you agree with, and surface the most load bearing points that challenge your initial opinion.

This process allows you to skip the points you agree with and surface the most load bearing points that challenge your initial opinion.

This can also be seen as an interactive unpacking of a Sazen, a short sentence compressing a precise insight. It is obvious to those who have it but puzzling to people who have never gone through the process of having the insight.

Content cairns.

After interacting with the socratic content, your contributions are added to the memory of the article. Your own arguments and counterarguments might be presented to new readers. As the article is read more frequently, the content integrates these contributions.

The initial author retains some editorial power. For instance, they can decide whether a certain disagreement counts as a valid limitation of the article or if it should be treated as a misinterpretation.

Some content cairns take a life of their own such that it doesn’t make sense to say they have been authored by anyone. They are living memes that gain life every time they are used, are tagged in online conversations, and respond without being bound to any platform.

Content to frame.

You just finished the excellent “On Green” by Joe Carlsmith. You learned the color / value association from Magic the Gathering: White: Morality. Blue: Knowledge. Black: Power. Red: Passion. Green: environmentalism? It’s complicated, that’s what the article expands.

You are interested in using this association in another context, and you add the essay to your frame library. Weeks later, you read the review of Seeing Like a State, a book about the limits of the high modernist, centralized state and the merits of local knowledge rooted in practical experiences. The “On Green” frame awakens and colors different parts of the article: the drive for control from the USSR in black, the need for making the territory legible through maps in blue, while the discussion of local knowledge is in green.

Multi-source content patchwork.

Instead of reading newsletters and social media feeds in silos, you read a single thread of content that smoothly integrates excerpts from long-form pieces with short tweets. AI news seamlessly gives way to the economic trends, which transitions into political discourse.

At the end of the thread, you have a good overview of the information landscape of the day and can decide which sources are worth digging into further.

Inspiration: Zvi Mowshowitz’s AI newsletters

No-screen online interface.

Every morning, you receive a newspaper made just for you. It contains a curated version of your social media feeds and newsletter subscriptions. You can use a barcode scanner to give feedback on the curation process to signal what you liked. You can also write on the newspaper, and the same barcode scanner will take a picture of your handwritten response and post it as a comment in the right place. Using the same mechanism, you can also publish handwritten pieces to your personal blog.

Some online creators have decided to go all the way and work in a no-screen online environment. They specialize in discussing slow-moving cultural trends, calling themselves the “trees” of the online ecosystem.

Inspiration: The Screenless Office, DynamicLand

Want to hear when I post something new?